Look, I'm actually quite a chill person, OK? (Shut up, members of my inner circle.) Yes, I can get a bit enervated by pretty much anything, and - OK - it would be fruitless to pretend that I don't have strong opinions. But as any trashy-romance-novel connoisseur knows, that just means I'm "passionate", "feisty", "firey". (And probably running from the law / about to solve a crime / in the midst of untangling a hunky cowboy's tragic history and showing him how to love again.) In case you hadn't realised by now, dear reader, I take my media consumption equal parts seriously and frivolously. I adore watching TV for its innate (mindless) pleasures as much as I adore analysing the fuck out of TV shows, unpacking what they do and how they do it. The vast majority of the time, these two activities occur sequentially: watching --> analysing. That way, I get to have my televisual cake and eat it too, as the near-unparalleled joy of getting totally absorbed in a show gives way organically, a little while after the credits roll, to my geeky analytical pre-occupations. But. This neat little flow-chart breaks down in cases of what I term "Crimes Against Medievalism". And it is in light of such Crimes, I admit, that I - to use the appropriate jargon - pointlessly lose my shit.

Given how niche the medievalist discipline is within academia, our lofty field does crop up a disproportionate amount of times on TV. Nevertheless, at least the media portrayal of medievalists and our primary material is authentic. My colleagues and I are, practically daily, central to solving various crimes, smuggling antiquities, laundering money willy nilly (for a juicy cut). All whilst we rewrite global histories on the basis of our minute attention to the symbology of just-discovered manuscripts. Simples! Oh wait, that was a fever dream I had when struck down by a killer bout of flu last year. My bad. Finally, I get what hard-done-to forensic scientists must have felt when CSI (and its various insidious spin-offs) "showcased" their working praxes. As long as you put The Who on, and do some weird close-up shots to reveal impossible levels of detail, you can solve ANY crime! Crimes Against Medievalism, in essence, cause medievalists - or at least this medievalist - to vent their spleen at the screen, a cathartic outpouring of utterly futile rage at how we are mis-represented in the media. Or, how people just DO THINGS WRONG with manuscripts, and medieval stuff. So, this post is the first in a new series in which I channel my pointless rage your way, dear reader. Yes, I know, I am kind aren't I? You're welcome!

With this backdrop, may I present to you the horrors of White Collar, SO1E03 (2009), "Book of Hours". Here is a synopsis of the episode:

On a routine stakeout of a well-known mob hang out, Agent Cruz and Agent Jones get a surprise visit from Leo Barelli, the local mob boss. Someone stole the bible from Barelli's church, and he wants it back...badly enough to come to the FBI for help.

Peter and Neal soon discover that this is no ordinary bible. Over five centuries old, the book is rumored to have the power to heal the sick. Peter is skeptical, but Neal knows there are true believers out there. Neal's theory leads them right to the culprit: Steve, a homeless veteran who took the bible to save his sick dog, Lucy. As it turns out, Steve was actually hired to take the bible by none other than Paul Ignazio, Barelli's nephew. [...]

Neal and Mozzie investigate Ignazio's apartment and come up with Maria Fiametta, a local art historian who is familiar with Neal's past exploits. Peter thinks Maria has something to hide, but she's just too smart to keep the bible close. If Neal convinced Maria he was coming out of retirement, would she give up the book? There's only one way to find out, but for Peter it means putting all the cards in Neal's hands.

I am ignoring the mystical woo element of the manuscript-as-healer narrative arc, which suggests that homeless veterans with PTSD don't necessarily need tailored services and support to get off the streets and re-integrate into society. Nope, just give them a dog (healthy preferred), and access to a miraculous manuscript! Problem solved!! Anyway. Because I have a life, I have summarised my key points of medievalist contention with the episode in the form of three handy images, Figs. 1-3 below.

Fig. 1. Red wine is bad for manuscripts. FACT.

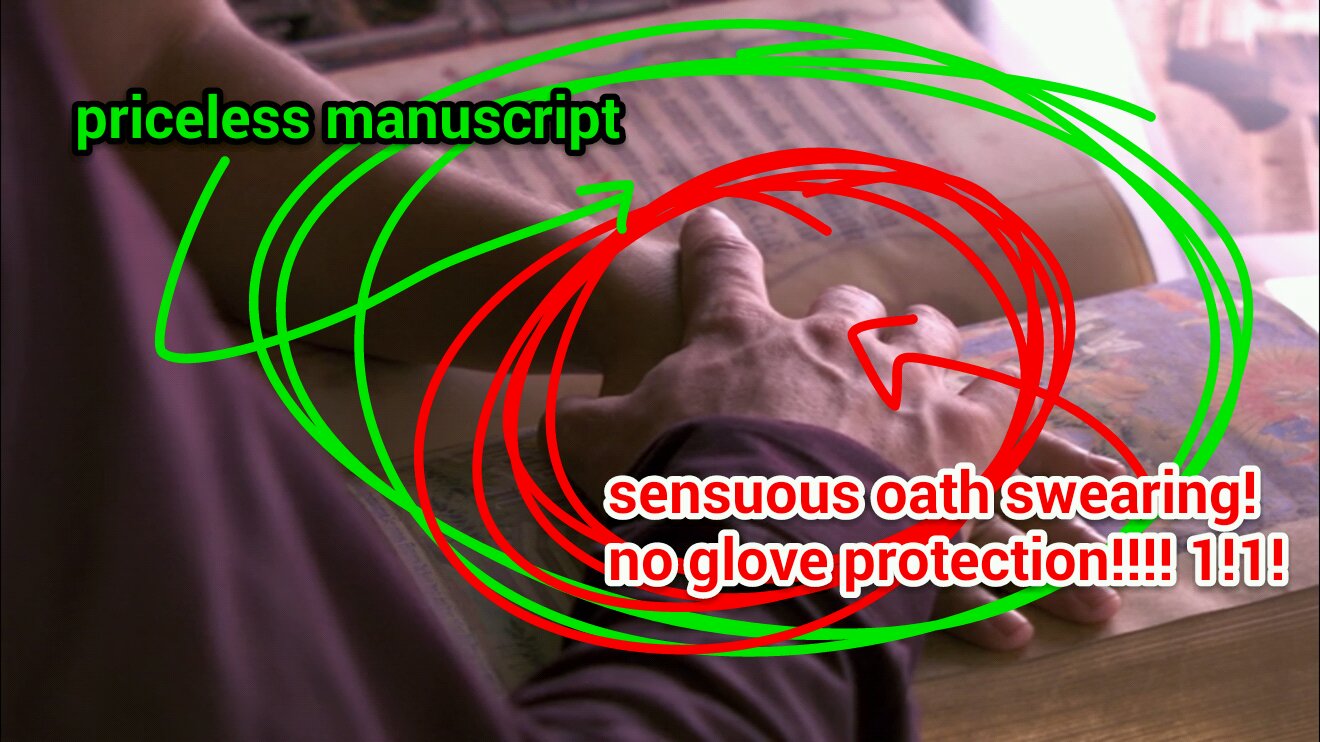

Fig. 2. You don't know where those hands have been. I swear I see oil and dermal debris.

Fig. 3. Somewhat bizarrely, manuscripts are not regularly used by the military as shield devices.

A while back, in the immediate aftermath of my White Collar rage, I posted these Figs to Twitter. Somebody - forgive me, I can't find the tweet now - pointed out that, actually, donning white gloves is no longer standard operating procedure for handling manuscripts. The British Library, for example, is quite clear:

Clean dry hands, free from creams and lotions, are preferable in the majority of circumstances. Wearing cotton gloves when handling books, manuscripts or fragile paper items reduces manual dexterity and the sense of touch, increasing the tendency to 'grab' at items. The cotton fibres may lift or dislodge pigments and inks from the surface of pages and the textile can snag on page edges making them difficult to turn. All these factors increase the risk of damage to collection items.

Members of the public, nevertheless, routinely criticise the Library (and its staff-members) when they see or read about artefacts being handled sans gloves. White gloves signal a cautious, professional touch honed by years of training. They operate as a kind of visible reverence for the manuscript being handled. This object is so important, so rare, that you have to wear gloves to touch it. More than that, the gloves speak a kind of privilege: you have to adopt the metaphorical - and artificial - "skin" of intellectualism just to come into contact with it. It turns out my rage at the absence of white gloves in the White Collar episode is, perhaps, even more pathetic than the usual impotent Crime Against Medievalism reaction. Digging a little deeper, I am astounded - and let's face it, a little jealous - to see manuscripts treated as fairly routine objects that you have at home. This is not my experience, visiting my lovely manuscript friends in various well-policed libraries over the years. I am not a private collector; a priceless manuscript will never adorn my desk, ready and waiting for disastrous wine spillages.

As Neal and Maria by turns flirtatiously stroke and chuck around the manuscript (Figs. 2-3), I'm struck that they seem to adopt the role of (moneyed) medieval expert without a second thought. Not so for the usual medievalist, whose skills have been honed over years of study and work, a period marked more and more by long hours and low pay. The white gloves would sort of suggest that we're "special" in some sense - again, that sense of a touch not normally accessible to those without our career devotion and sacrifices. And then! Neal puts on some damn gloves - but he's not supposedly the expert in this narrative, Maria is. Maria, who is about to shoot a man THROUGH A PRICELESS MANUSCRIPT. Jesus wept. I'm not quite sure what I think, where my rage is going, after working through this a bit more. Given the dire state of the medievalist job market (just a sub-section of the appallingly difficult academic job market), perhaps I wanted to see some kind of validation of the skill-set of medievalists, a sign of our "special-ness" that would suggest we, and our work, are needed. Don't panic, though, it's not all maudlin self-reflection, I've still got the medievalist rage. As such, I leave you with the following take-aways:

- A generous red wine soak will not make your manuscript better, tastier, nicer to look at.

- As a rule of thumb, I suggest that you don't use your priceless manuscript as a bullet-proof vest. Sure, the British Library don't expressly forbid it, but I am 78% sure it is implicit in their code of conduct.

- If you want to go glove-free - as well you should when touching priceless manuscripts - please ensure your hands are clean, dry, and free of the cloying schmutz of painful exposition.

- In conclusion, white gloves are a land of contrasts.